Naming the legacy of slavery

As statues of those tainted by slavery tumble down across England and the United States, and the Municipality of the Township of Russell, Ontario, casts about for a namesake to replace the lamentable Peter Russell, might Perth contemplate how far the historic stain of human bondage extends? Could connections to slavery sully our streets and landmarks as well?

Who qualifies for censure as a perpetrator of slavery? Clearly those who personally or corporately owned and profited from slaves are condemned? But what of those who may not have owned slaves themselves, but still aided and abetted the cursed institution? Are they equally guilty? Perhaps even a society at large, that for centuries accepted and benefited from slavery, bears the same burden of guilt as the whip-in-hand slave master? Where does culpability begin and end?

Peter Russell (1733-1808) was a one-time junior officer in the British Army, with a gambling habit that drove him into bankruptcy, who so wormed his way into the good graces of Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe (1752-1806) that he was appointed Receiver General and then Administrator of Upper Canada while Simcoe was absent on leave in 1796-1799; during which time Russell took the opportunity to appoint himself a judge on the Court of King’s Bench (even though he had no legal training whatever). All of that might be enough for the Ontario village, Township and County bearing his name to seek out a new ‘Russell’ as patron, but it is Peter Russell’s ‘ownership’ of four slaves, a woman and her three children, that led to the Township Council’s recent 3-to-2 vote in favour of casting him onto the dung heap of history.

Peter Russell was, of course, a man of his time in an age when the British Empire was reaching the peak of its economic and military power on the back of a massive slave labor force. Enforcing the subjugation of hundreds of thousands of human beings demanded the constant threat and frequent application of deadly force, a level of coercion far beyond the means of the comparative handful of planters, merchants and corporate shareholders who actually ‘owned’ the slaves. In the ‘sugar islands’ of the West Indies that meant the British Army.

While military garrisons served to defend the islands against attack from Britain’s perennial enemies France and Spain, the troops were more often called upon to defend slave owners against revolt by their bondsmen. They enforced the institution of slavery, crushed any spark of resistance, and ensured the men and women in bondage remained ‘in their place’.

Among the soldiers who ensured that the slave masters of Barbados, Bermuda, British Honduras, Jamaica, St. Vincent, and Tobago slept soundly in their beds were at least eight of the men honored today at the street corners of Perth.

Provost Street

Sir George Prevost (1767-1816), for whom Provost Street is named, commanded the St. Vincent garrison as Lieutenant Colonel of the 60th Foot in 1794-1795. Guarding against any attempt by St. Vincent’s slaves to shed their chains was a constant; there had been a slave revolt on St. Vincent in 1769-1773 and, shortly after Prevost left the island, there was another in 1795-1796.

Gore Street

From 1804 through 1806 Francis Gore (1769-1852), a retired Army Major, for whom Gore Street is named, served as Lieutenant Governor of Bermuda. The island was not home to the large plantations found elsewhere in the West Indies, but about 6,000 slaves still did most of the vital work as sailors, carpenters, coopers, blacksmiths, masons, and shipwrights. As six slave revolts over the previous 150 years demonstrated, a significant responsibility of Governor Gore and his staff, backed by the local garrison, was the prevention of similar rebellions.

Halton Street

During the years Francis Gore served as Governor of Bermuda, he was supported by his Principal Secretary, and head of his administrative staff, retired Army Major William Matthew Halton (1769-1821), for whom Halton Street is named.

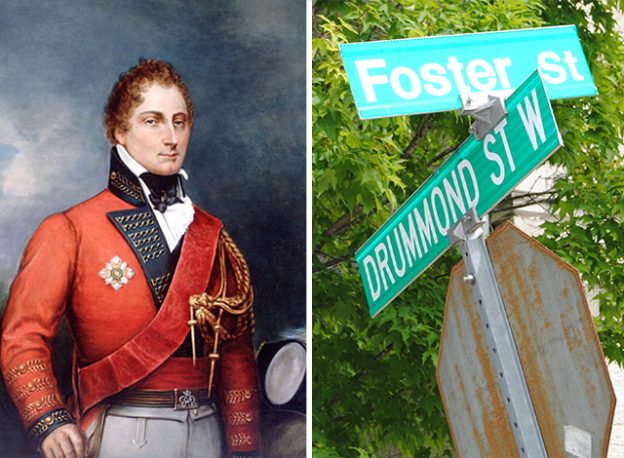

Drummond Street, Drummond Township

Suppressing any attempt to achieve freedom on the part of Jamaica’s slaves demanded frequent resort to military force. There were at least 20 slave rebellions between 1655, when Britain seized the island from Spain, and emancipation in 1833.

Sir Gordon Drummond (1772-1854), for whom Drummond Street and Drummond Township are named, served seven months garrison duty in Jamaica in 1789, as an Ensign of the 1st (Royal Scots) Regiment of Foot, and then returned to the island, 1806-1808, as Colonel of the 8th Foot. During Drummond’s second tour of duty troops suppressed a rebellion plot in Saint George’s Parish in 1806 and in 1808 put down another plot in Kingston and a mutiny among slave-soldiers of the 2nd West India Regiment.

Foster Street

At the time of the 1806 and 1808 Jamaican slave revolts, Colonel Colley Lyons Lucas Foster (1778-1813), who gave his name to Foster Street, was playing his part as aide-de-camp and military secretary to the colony’s Lieutenant Governor Sir Eyre Coote and then secretary to the island’s Governor, William Montagu. Foster served on Jamaica from 1804-1811.

Brock Street

As a Captain in the 49th Foot in Barbados in 1791-1792, Sir Isaac Brock (1769-1812), for whom Brock Street is named, ensured no recurrence of the seven slave revolts that had swept that island in the late 17th century; a real possibility, as demonstrated by an eighth rebellion in 1816 after the 49th Regiment had been transferred to Jamaica and then Canada.

Brock served on Jamaican in 1792-1793 ensuring that island’s white planter and merchant class were safe from the retribution of their slaves.

Robinson Street

Robinson Street is named for Sir Frederick Philipse Robinson (1763-1852), the descendant of a slave owning family from Middlesex County, Virginia, who was Governor and Commander-in-chief of the island of Tobago from 1816 through 1828, guarding against a repeat of five slave uprisings that had shaken the island over the previous 50 years.

Cockburn Street, Cockburn Island and Cockburn Creek

Cockburn Street, Cockburn Island and Cockburn Creek are all named for Sir Francis Cockburn (1780-1868) who served as Superintendent of the colony of British Honduras from 1830 through 1837 at a time when nearly three quarters of the colony’s total population were enslaved. Slavery in British Honduras was associated with the extraction of timber rather than plantations so, with freedom more easily attainable by slipping away into the bush, slave revolts were less common than on the sugar islands. Nevertheless, Cockburn had to maintain a firm hand as there had been at least four uprisings in the colony in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Emulating the sugar planters, the British Army itself engaged in slave ownership. Between 1795 and 1807 the Army filled the ranks of eight all-Black regiments by purchasing 13,400 slaves from West Indian plantations and arriving slave ships. In circumstances where Yellow Fever killed White troops by the thousands, Black troops were found to be of hardier constitution.

Among those names on Perth’s street signs, only Drummond had any direct experience of the slave regiments and, unlike Peter Russell, none of them seem to have ever owned a slave personally. They would, however, have enjoyed the services of slaves owned by others; slaves assigned to tasks around the garrison, to serve in the officers’ mess and, in some cases, to work in their homes.

More importantly, their position as British Army officers serving in the West Indies placed them squarely in roles just as essential to keeping men, women, and children in lifetime bondage as that of the plantation overseer with his whipping post. Without their participation and that of the troops they commanded, slavery on the West Indian plantations could never have been sustained. Except by the application of deadly force, how could less than 50,000 whites manage to keep nearly ten times their number of Blacks enslaved?

| Island | Slave | Freedmen | White | Total |

| Bahamas | 9,991 | 1,204 | 3,306 | 14,500 |

| Barbados | 74,990 | 2,512 | 15,538 | 93,040 |

| Bermuda | No Data | No Data | No Data | No Data |

| British Honduras | 2,899 | 1,000 | 201 | 4,100 |

| Jamaica | 346,399 | 29,911 | 27,890 | 404,200 |

| St. Vincent | 27,402 | 1,313 | 1,134 | 29,850 |

| Tobago | 1,993 | 804 | 804 | 19,600 |

| Total | 479,674 | 36,744 | 8,872 | 565,290 |

Yet, all men and the lives they live are multidimensional.

As Governor General and commander of British forces in North America 1811-1815, Sir George Prevost directed the successful defence of the Canadas during the War of 1812. In 1814, Isaac Brock and his 49th Foot turned back the American attack at Queenston Heights and Gordon Drummond’s little army fought U.S. forces to a standstill at Lundy’s Lane. Colley Lyons Lucas Foster was twice mentioned in dispatches for his part in the War of 1812. Without these men Donald Trump might be our President today.

Francis Gore may have been “the most incompetent and disliked Lieutenant Governor in the history of Upper Canada” but his administration did establish a system of common and grammar schools, helped ready the colony to face American invasion in 1812-1814, and implemented the colony’s first program of public road construction. Gore’s secretary, William Halton, was an advocate for the welfare of veterans of the War of 1812 and their families, and for the settlement of United Empire Loyalists in Upper Canada.

Before his posting to British Honduras Francis Cockburn played a leading role in creating new lives for thousands of immigrants escaping bitter poverty in Britain. As the British Army’s Deputy Quartermaster-General for Upper and Lower Canada he established and provisioned the military settlements at Perth, Richmond, Lanark, the Bay of Quinte, Glengarry County and Rivière Saint-François.

Even Russell Township’s (former) namesake, Peter Russell, was not entirely without merit. During his regime in Upper Canada, he was an outspoken supporter of First Nations’ rights when they had issues with encroaching white settlers, and he attempted to reform the system of land grants in order to curtail rampant speculation, nepotism, and corruption.

Therein lies the dilemma of slaves, statues, and street names.

While their accomplishments and contributions to Canada’s early history placed their names on Perth’s street signs, does reconsideration of their part in perpetrating slavery dictate their names should now be replaced – as in the case of Peter Russell?

Or should we recognize this as a ‘teachable moment’, through which we may contemplate and acknowledge the complexity of so-called ‘great men’ and the general untidiness of history.